Big Gifts That Keep On Giving to Local Economies

February 13, 2018 | Read Time: 5 minutes

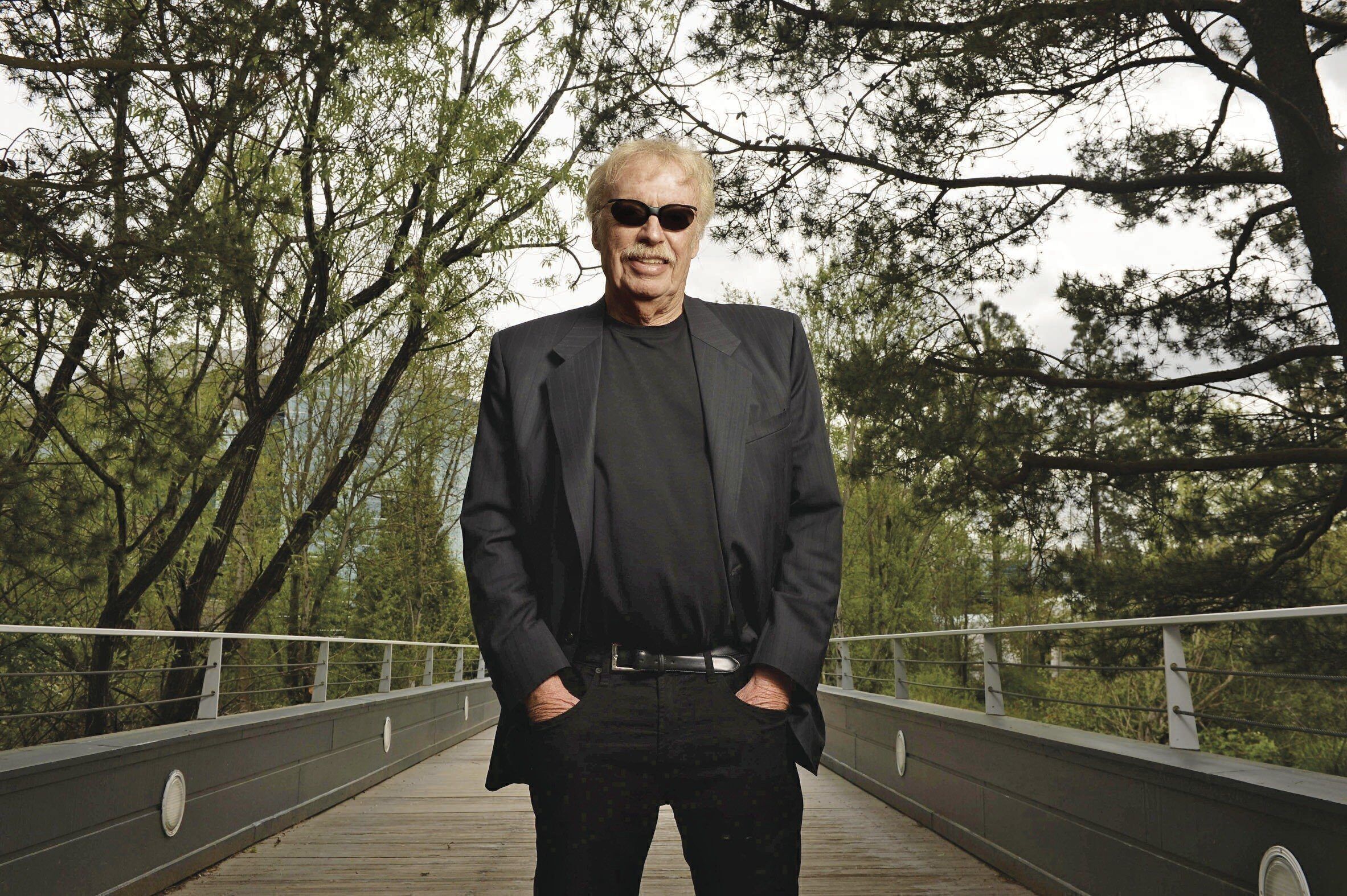

When the University of Oregon announced a $500 million gift from Nike co-founder Phil Knight and his wife, Penny — a gift that landed him on top of last year’s Philanthropy 50 — officials spent nearly as much time talking about its impact on the local economy as on the university itself.

Construction of the Phil and Penny Knight Campus for Accelerating Scientific Impact and its annual operations will contribute to the Eugene, Ore., economy, officials say. And that’s not counting the possible upside from the commercialization of university research.

“If you spin out a Google, then all of a sudden your economic impact is incalculable,” says Patrick Phillips, the campus’s acting executive director.

- ‘Forbes 400′ and ‘Giving Pledge’ Billionaires Who Gave Big in 2017

- Philanthropy 50: Where They Live, Where They Give, and More

- America’s Superrich Made Near-Record Contributions to Charity in 2017

- The Chronicle Digs Deep to Compile Annual List of Top 50 Donors

- That $33 Million Bezos Gift for Dreamers? It Started With a Tweet.

Economic development is rarely a primary focus when donors make megagifts, but big dollars do have the potential to transform communities, especially small cities. Large gifts to charities and institutions in Indianapolis, Sioux Falls, S.D., Elkhart, Ind., and Newtown, Mass., are boosting local economies, according to charity leaders and economic experts.

While big gifts may have the most noticeable impact on cities the size of Sioux Falls or Eugene, economy-oriented gifts are likely to get a higher return on investment in larger urban areas, says a Brookings Institution researcher. Research-oriented gifts to “downtown” universities lead to greater commercial results due to their proximity to entrepreneurs and other businesses, says a new paper by Scott Andes, a Brookings fellow.

Mr. Andes found that the downtown universities outperform institutions in suburbs and rural areas on licensing deals, licensing revenue, inventions, and start-up creation.

“In an ideal universe, allocating philanthropic capital to its highest return, we would obviously see different types of donations,” he said in an interview. “A lot of folks are contributing based on personal relationships and places they have affinities to, but that doesn’t mean those are the best places to park money.”

Hoping for More

The charities that are most likely to track and document their economic impact are those that hope to tap into even more money from philanthropists and legislators who care about a vibrant economy.

In addition to their $500 million pledge to the University of Oregon, the Knights also made a $500 million commitment in 2013 to the Oregon Health & Science University for the Knight Cancer Institute.

Both universities hired ECONorthwest, a consulting firm, to conduct an economic analysis of the projects — calculating statistics such as the number of jobs created and the annual financial impact on the local economy. The OHSU study helped the Portland institution persuade legislators to issue $200 million in bonds for new buildings at the cancer institute.

The University of Oregon is likely to receive most of the $100 million in state bonds that it sought, too — and that’s because state leaders are seeing that the university is serious about contributing to economic growth, Mr. Phillips says.

Gwen Walden, a senior managing director at Arabella Advisors, a philanthropy-advising firm, says it’s important to track whether the economic impact envisioned by donors and nonprofits actually occurs. The anticipated impact may fall short, she notes, just as the philanthropic goals of donors sometimes fail to materialize.

“It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and the intentions, but the devil is in the details — you have to get the implementation right,” Ms. Walden says. “That’s where many of these large gifts may falter and where the projections of the economists may turn out not to come true.”

Hard to Measure

Gauging economic impact is all the more difficult because some of the most significant results are challenging to measure. In 2015, the Salvation Army hired Partners for Sacred Places to assess the economic impact of its Kroc Centers — state-of-the-art facilities, often in needy communities, that combine religious services with gyms and swimming pools.

The charity has opened 26 centers throughout the country after receiving a bequest from the estate of Joan Kroc in 2004 worth $1.5 billon. Partners for Sacred Places was able to estimate how much a typical visitor to a Kroc Center might spend at a local gas station or restaurant, and even place an economic value on the improved health that regular gym visitors enjoy.

What’s more difficult to assess is whether the very presence of a Kroc Center elevates an entire neighborhood, leading to increasing home values and a decrease in crime.

Tuomi Forrest, Partners’ executive vice president, says such improvements are happening around the Kroc Center in the Hunting Park neighborhood of Philadelphia, not far from the Partners for Sacred Places office. But he says the organization would need to conduct a longitudinal study to isolate the impact of the Kroc Center on the neighborhood’s rise.

“We tackled a lot,” Mr. Forrest says. “But there’s more to be investigated.”

Faulty Projections

In 2012, Steven Peterson, an assistant clinical professor of economics at the University of Idaho, wrote a report for the Philanthropy Collaborative that found that foundation grant making contributes more than $570 billion to the U.S. economy over the long term. Mr. Peterson and other scholars have found that gifts that advance scientific knowledge, improve health outcomes, and revitalize inner cities have especially high rates of economic return.

Similar outcomes probably hold true for gifts by individual donors, he says, but that doesn’t mean that donors with a passion for art or preserving biodiversity should shift their giving to try to generate a greater economic impact. The economic impact is tied to long-term projections that — as Ms. Walden noted — do not always come true.

“Donors should follow their calling,” Mr. Peterson says. “For a lot of this work, the economic benefits are really the icing on the cake. They’re not the cake itself.”