Can Documentaries Change the World for the Better?

October 6, 2014 | Read Time: 5 minutes

News that Participant Media, an entertainment company that produces movies with a social message, has joined with the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School and several foundations to develop better measures for figuring out whether media projects are succeeding in spurring social change has won big applause. Many grant makers and others see the action as an important form of due diligence.

But the new venture also raises tough questions that donors and advocates need to consider. Among them:

- What does social change mean, and is it the same as social impact? How do you convert short-term impact to lasting change?

- As Albert Einstein asked, can everything that counts be measured? And just because something can be measured, does that make it count?

- Is there a difference between art and advocacy?

Foundations spend billions of dollars a year trying to improve the world, so they naturally worry about whether their money is making a difference.

Grant makers that support media projects, like the Gates, Knight, and Soros foundations and the for-profit Participant Media, tend to advocate for specific causes: reducing carbon emissions to mitigate the effects of climate change; improving education by supporting one type of school or pedagogy over another; saving endangered species and preserving wilderness areas; fighting poverty and inequality; reforming health care; and so on.

Many of these grant makers have grown concerned that they may be preaching to the choir and their media projects are not creating the social change they desire. They seek more rigorous analytics, an index that would allow them to more effectively measure, and potentially recalibrate, their messages to their target audiences.

Better metrics can help shape media projects, but activist grant makers with a social-change agenda must avoid social engineering and confusing art with advocacy because they could turn off their audiences or elicit unintended consequences.

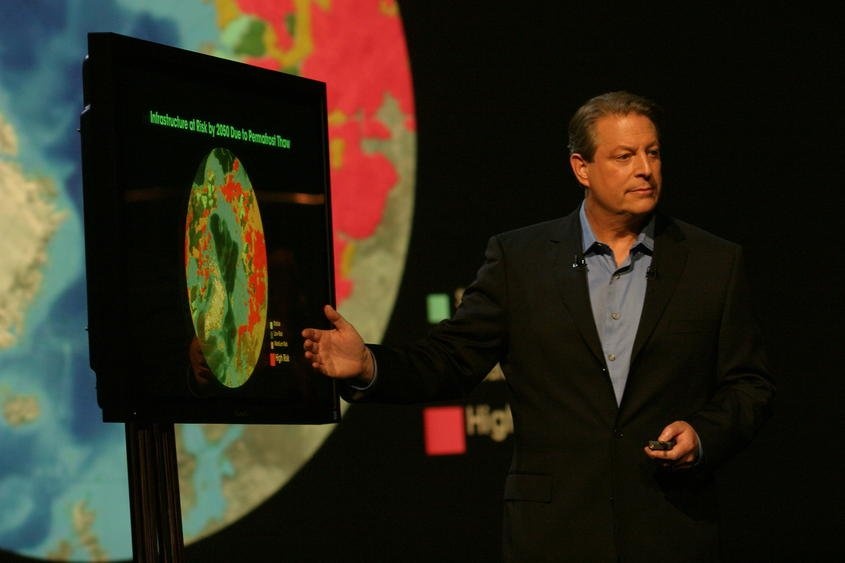

For example, the Al Gore film “An Inconvenient Truth” won the Oscar for best documentary and deserves credit for raising international awareness of global warming. It is rightly considered a signal success for social-impact media.

But some analysts have since raised questions about what change the film engendered because the number of people who believe in global warming has not significantly shifted since the film came out, while partisan polarization about climate change has increased. One study found that two years after the film, the split between Democrats and Republicans reporting that they personally worry a great deal or a fair amount about global warming rose by more than one third.

It’s possible that “An Inconvenient Truth” reinforced the views of liberal Democrats who were already inclined to believe in global warming—even if they didn’t know it—but the film did not reach people, mostly Republicans, who were skeptical or disliked Al Gore’s politics and tuned him out.

This can be a challenge with advocacy media in general when it argues, often quite cogently, for one set of partisan views but does not always convey the whole picture as it strives to evoke a specific emotional response and, increasingly, to target specific action by each viewer. An alternative approach is to take a nonpartisan position on controversial issues and try to present a fully rounded portrait, acknowledging uncertainty or trade-offs where they exist, thus empowering viewers to make up their own minds.

Intensive research on every aspect of viewer response and the resulting big data promised by this new venture can yield insight, but it can also lead to “algorithm dependence.”

If “The Square,” a documentary about the Egyptian revolution, scored lower on “provoking action” than another film, does this make “The Square” a lesser work or less likely to lead to social change over time?

Grant makers must interpret and tease apart the data. Does the fact that “digital intellectual-property issues” ranked at the very bottom of a list of 40 primary concerns on the Participant Index make it any less critical an issue for society? Foundations should lead, not follow.

Another challenge is that most advocacy issues—climate change, education, poverty, and disease—are deep-rooted, long-term problems, and crafting appropriate solutions is a long-term challenge. A film or a television show may attract a big audience or win plaudits, but even if it gets you to write a letter to your member of Congress or boycott a company’s product—the kind of measures many donors use to judge a project—it is unclear whether this will lead to long-term social change.

Asking people their emotional response and level of engagement after viewing a film is interesting, but it would be more useful if it was followed up by similar questions at three- or six-month intervals over several years. And even this caveat ignores the truism that art works in mysterious ways. Twitter, Facebook, and online surveys, wonderful as they are, may still be very blunt instruments when it comes to measuring the awakenings of the soul.

Like investors overly concerned with immediate quarterly results, grant makers who focus primarily on specific short-term actions resulting from films may risk ignoring the more profound ways that works of art can affect people and influence the culture in which we are all embedded.

“If you want to send a message, use Western Union,” Sam Goldwyn famously quipped.

Foundations are major patrons of the arts and have supported many great artists and arts organizations. But the role of grant makers in underwriting artistic work must respect the creative process and the open-ended journey of discovery that each viewer embarks on.

Backing a film or television show whose primary goal is a single measurable action or reaction in the viewer may lead to short-term impacts, narrowly defined and now rigorously ranked, but it is less likely to lead to illumination or the long-term social and cultural changes that can arise from deeper engagement. For that you need to trust the artist’s individual vision, trust the unfettered artistic work, and trust your audience to think for itself and not be spoon-fed pre-selected conclusions.

Doron Weber is an author and vice president for programs at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and has focused on making grants for science-themed film, television, theater, and other media for nearly two decades.