8 Things a Mega-Donor Did Right to Engineer a ‘Miracle’

How $160 million from Netscape pioneer Jim Barksdale — a newcomer to social-change philanthropy — helped make schools in his native Mississippi a source of pride, not shame.

July 29, 2025 | Read Time: 10 minutes

Keep up with everything happening in The Commons by signing up for the Chronicle’s Philanthropy Today newsletter or our weekly Commons LinkedIn newsletter.

It started, as many philanthropic efforts do, with a wealthy business executive brandishing an oversized check and promising sweeping change. “This program will and must work,” he declared, standing on a stage as news cameras rolled.

The ambition echoed that of other high-profile, big-money ventures that now lie in the graveyard of philanthropy deemed a failure. The executive pledged an overhaul in education, a field that has stumped mega-donors like Walter Annenberg (who championed “model” schools and districts in the 1990s), Bill and Melinda Gates (small schools and teacher evaluations in the 2000s and 2010s), and Mark Zuckerberg (turnaround of schools in Newark, N.J., in the 2010s). Moreover, he was working in Mississippi, where deep poverty and racial inequality routinely snuff out well-intentioned efforts.

But 25 years after Jim Barksdale stood on that stage, it’s clear that the Mississippi native son, corporate titan, and Silicon Valley entrepreneur beat the odds. Motivated by his childhood struggles to read, Barksdale and his wife, Sally, pledged $100 million to boost literacy — a sum that would grow significantly. Over time, the nonprofit they created built a reading-instruction model that became an anchor in a state plan to boost literacy that included significant new dollars — an instance where philanthropy’s experimentation persuaded government to take an idea to scale.

A decade ago, the state ranked 49th in reading proficiency among fourth-graders. Today, it stands ninth. Mississippi’s low-income students have the highest scores of their peers in any state.

“It’s a powerful example of what’s possible when we in philanthropy and public leadership move in the same direction,” says Rhea Williams-Bishop, a fifth-generation Mississippian who leads the Mississippi and New Orleans programs for the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

This turnaround has been dubbed the “Mississippi Miracle,” which is perhaps a bit grandiose. Critics suggest the gains may be exaggerated. By eighth grade, Mississippi students are again posting reading scores near the bottom of the national pack. Also, other factors contributed to the gains, including a 2013 law that requires third-graders be proficient in reading before moving to fourth grade — legislation that Barksdale initially opposed.

Still, the Barksdale effort is credited with helping to transform reading instruction in the state, deepen the state’s investment in literacy, and create common ground in education — one of the most polarizing issues in the country. New public confidence in schools has helped blunt momentum for school-choice programs popular in other Republican-dominated states in the South, says Lloyd Gray, a former journalist who covered education and politics in the state for nearly 50 years. Also, local school boards have mostly avoided the culture wars roaring in districts nationally.

“Mississippi has such an inferiority complex and has for so long just considered itself at the bottom of everything,” says Gray, who now leads the education-focused Phil Hardin Foundation in the state. “To get attention on this issue is a real boost.”

What Did Barksdale Do Right?

To identify the essential components of Barksdale’s success, we spoke to key players, as well as others who followed the work:

Establish a single, clear objective. Don’t waver. Barksdale is fond of a business and philanthropy maxim: “Keep the main thing the main thing.” From the outset, he focused on increasing fourth-grade scores on the National Assessment of Education Progress. He liked that it was a simple measure, and research suggests reading proficiency by the end of third grade predicts academic success.

While Barksdale faced considerable pressure to expand to work with older students, he largely resisted.

Be dogged about data. Barksdale’s business career included stints as a top executive at FedEx and as CEO of Netscape, one of the first billion-dollar internet start-ups. He and Sally (who died in 2003) had donated millions previously — including to his alma mater, the University of Mississippi — but this was his biggest gift and his first aimed at engineering social change.

Barksdale describes the donation as an investment, and he deployed tactics typical of business ventures. You can’t manage what you can’t measure, he says. “We were always testing and saying, ‘Prove it.’” At the same time, he recognized that some things can’t be measured. “How far can you push to get accurate and reliable measurements?”

Test and evaluate. Test again. At the outset, Mississippi officials asked Barksdale simply to fund expansion of a state program that introduced reading specialists to low-performing schools. He agreed, but instead of giving money to the state, he set up a nonprofit — the Barksdale Reading Institute — that became a de facto research and development arm to determine how best to teach reading.

“We became, as I like to refer to it, the engine of science for the state,” says Kelly Butler, who joined the institute in its early days and later became its executive director. Thanks to the organization’s autonomy from the state, it could chart its course largely free of shifting political winds and priorities as governors and superintendents turned over.

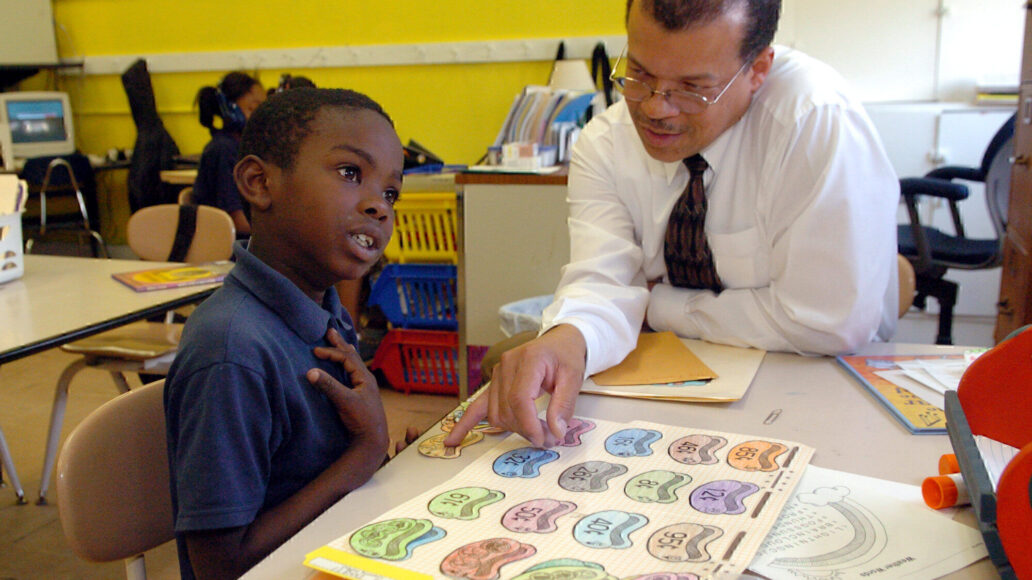

At the time, brain-imaging research from the National Institutes of Health had established that reading instruction should help students decode words through phonics — a study that accelerated a turn away from the dominant “whole language” or “balanced literacy” approach, which is championed by Columbia scholar Lucy Calkins and relies on cues and context. The institute leaned on those findings but also experimented with delivery of instruction. Its testing led to what’s called the “Barksdale model,” which includes a 90-minute literacy block in the morning and differentiated instruction for students.

The institute was more nimble than the state, says Kymyona Burk, a teacher when the Barksdale initiative began who went on to become Mississippi’s literacy director. “They were able to do these pilot projects to figure out what was working. If it wasn’t, they would just go somewhere else.”

Some pilots failed, including a program to create parent centers in schools designed to reinforce literacy instruction in students’ home life. “If it doesn’t work, don’t be too proud to quit,” Barksdale says in a video history of the institute.

Partner with affected communities. The institute owes its success in part to its top-down approach, Butler says. The state gave it leeway to implement its program, and in a few cases, the institute even took over control of schools.

The intervention wasn’t always welcomed by communities or by a teaching corps that resisted phonics. “We had one school picket us one day and said, ‘Go home, Barksdale,’” Butler remembers.

But the institute worked to build relationships within school communities, particularly through its coaches. And it used its data to persuade doubters. “I learned that some of the stuff that I was doing in my earlier teaching years wasn’t what was needed to get students on the right path,” says Erica Jones, a former elementary teacher and now the executive director of the Mississippi Association of Educators. “I do remember the Barksdales as partners in this work.”

Rely on experts. Claiborne Barksdale, Jim’s brother, ran the institute. A lawyer, he set out to turn himself and his staff into experts. Devon Brenner, a professor of teacher education at Mississippi State University, clashed with Claiborne Barksdale when the institute pushed for a required course in phonics, but she and other education-school colleagues forged a compromise.

“I feel like Claiborne had done his research and was incredibly knowledgeable about the challenges and the literature and the science,” Brenner says. Grant makers need to ensure they have deep expertise — preferably on staff — when trying to advance big change, she adds.

In hindsight, more research and analysis should have been done before work began in schools to learn what others had done, examine failures and successes, and “plan the attack,” Claiborne Barksdale says.

“Make sure you’ve got plenty of runway,” he advises other philanthropists.

Use political muscle and connections. Jim Barksdale gives money to Democrats and Republicans, and he’s liked on both sides of the aisle. Moreover, he backed Parents for Public Schools, a powerful state advocacy group, for many years. “In large public efforts, you have to get involved with the politicians who pass the laws and who monitor and administer the laws,” he says.

When the 2013 legislation aimed to hold back third-graders who aren’t proficient in reading, the institute initially worried it would wrongly punish students and teachers. But when passage became likely, it used its credibility and political clout to increase funding for instruction and reading coaches. Some institute staff went to work full time at the state to design the law’s implementation.

“They trusted us,” Claiborne Barksdale says. “They knew we didn’t have any ulterior motives.”

Stick to it. The institute closed in 2023, nearly a quarter century after Barksdale pledged the $100 million. Such long-term commitment is not the norm in philanthropy, where priorities routinely shift. That’s particularly true in Mississippi, says Burk, now an education policy fellow with ExcelinEd. Funders often launch pilots in the state to test a program with low-income students, then pull up stakes.

“You may see growth for a little while, as long as the money is there and the support is there,” she says. “But when those things are taken away, it really goes back to the same old thing.”

Says Jim Barksdale: “In hindsight, 20 years really isn’t that long when you’re doing something major like changing children’s ability to read.”

Spend what it takes. When the state initially asked Barksdale to back the state’s literacy pilot, the request was for a few million dollars. Barksdale countered with $100 million, reportedly saying, “I’d like to get this problem solved.” By the time the institute closed its doors, he had doled out roughly $160 million, according to Claiborne Barksdale. (A legacy project, Reading Universe, continues to offer teachers nationwide free resources.)

At several moments over the years, the Barksdales concluded that they needed to expand the work beyond the classroom to achieve impact. They spent money on an array of things: curriculum, coaches, teacher and school-leader professional development, education-school curriculum, training for higher-education faculty, advocacy, and more.

Claiborne Barksdale says his brother didn’t balk at the new outlays. “I don’t want to say we had a blank check, but it was pretty damn close.”

Reporting for this article was underwritten by a Lilly Endowment grant to enhance public understanding of philanthropy. The Chronicle is solely responsible for the content. See more about the Chronicle, the grant, how our foundation-supported journalism works, and our gift-acceptance policy.

The Commons is financed in part with philanthropic support from the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, Einhorn Collaborative, and the Walton Family Foundation. None of our supporters have any control over or input into story selection, reporting, or editing, and they do not review articles before publication. See more about the Chronicle, the grants, how our foundation-supported journalism works, and our gift-acceptance policy.