Giving Pledge Myths Debunked

Nearly a decade after its launch, it still inspires hype and hope. The fanfare gilds the reality of the results so far.

June 4, 2019 | Read Time: 4 minutes

The pledge is not as big as it might appear.

Of the 155 U.S. citizens on the pledge, 10 have died since they signed yet remain in the group’s official tally. That number includes six who joined in the first year, among them philanthropy legends Paul Allen, Peter Peterson, and David Rockefeller. (Five others have died, each the primary wealth earner in their family, but in each instance, the spouse is alive to carry on the philanthropy.)

The group’s roster has also received what you might call an artificial boost, its numbers fueled in some instances not by popularity but by changing family dynamics. Two married couples initially signed together — Bill and Karen Ackman, and Harold and Sue Ann Hamm — but each later divorced, with the wives going on the pledge separately by their maiden names, Herskovitz and Arnall, respectively. Also, John Michael Sobrato, who initially joined the pledge in 2012 with his parents, John and Susan Sobrato, signed on his own recently with his wife, Timi.

Many pledge members are not billionaires.

In news announcements and other material, the pledge has declared that it specifically targets billionaires, and the media frequently refers to the group as a billionaires’ club. Yet from the beginning, a significant number of signatories have not met that wealth threshold, at least by the Forbes annual estimation of net worth. Eleven of the first 40 were millionaires, not billionaires, the magazine noted in 2010.

Today, only 96 of the 155 U.S. signatories have 10-figure fortunes, based on the 2019 Forbes ranking of billionaires.

That number may underestimate the pledge’s concentration of billionaire wealth. As the Gates-Buffett team has noted, Forbes net-worth estimates can be vague and imprecise. Also, a few pledge members were billionaires when they signed but have dropped below that level since, perhaps due to their philanthropy.

T. Boone Pickens and Barron Hilton — two pledge members with a record of big gifts — are among five from the class of 2010 whose net worth no longer reaches the billion-dollar mark.

Still, the fact remains: By a widely accepted measure of wealth, about a third of pledge members are not billionaires.

//

This is not a group of America’s superwealthy.

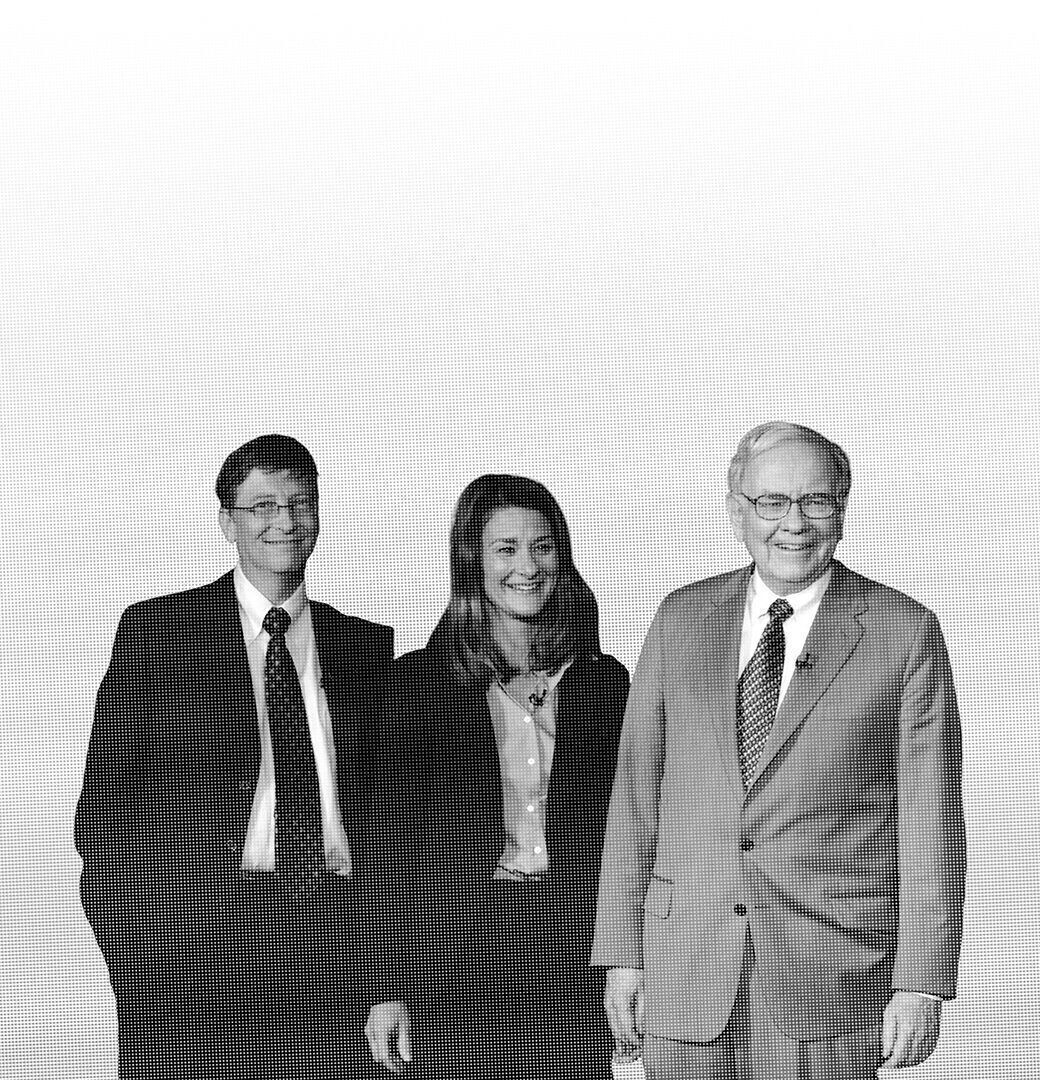

In its first year, the pledge roster of 57 could boast 42 signatories who held a spot on the Forbes 400 list of America’s wealthiest individuals. Buffett and the Gateses appeared to be recruiting from the top shelf of wealth. “We’re never going to get absolutely everybody on the [Forbes 400] list,” Melinda Gates told the Chronicle at the time. “We have to be realistic. What we want to do is get a crux of people.”

Such talk and early success fired imaginations and set expectations perhaps too high. Fortune writer Carol Loomis, a friend of Warren Buffett’s who chronicled the pledge’s birth, swooned at the possibility that every Forbes 400 member would sign up. Should that happen, she noted, at least $600 billion — half of the 400’s collective net worth — would be earmarked for charity under the pledge.

“You can think of that colossal amount as what the Buffett and Gates team is stalking — at a minimum,” she wrote.

But if Buffett and the Gateses are big-game hunting, their prey is elusive. The number of Forbes 400 members on the pledge has reached only 73 — just 31 more than it was that first year. The Giving Pledge, in other words, is most certainly filled with wealthy people, but many of the richest in America are keeping their distance.

The pledge has not evolved into the hoped-for philanthropy movement.

Buffett and the Gateses often say the pledge has grown larger than they imagined it would. But when it launched, others dreamed of something much bigger. “America’s billionaire Giving Pledgers are forming a movement,” declared the Economist in 2012. Brad Smith, head of what was then the Foundation Center, wrote a blog post arguing that the Giving Pledge and Occupy Wall Street, while radically different, were both social movements.

These and other analyses saw in the pledge’s early momentum the seeds of a new, much more robust and effective philanthropy, thanks to the combined smarts and wealth of the pledge’s titans of industry and other people.

Today it would be hard to call the pledge “a movement” when only one out every six billionaires in America belongs.

Oddly, the pledge enjoyed its heyday for growth while the country was still shrouded in the Great Recession’s shadow. Now, despite the sunshine of a long economic expansion that has enriched the wealthiest in America, it is an enterprise still outside the billionaire class looking in.